I had to have a one-day cool down before trying to write something about what just happened. I still have a headache. I still can’t grasp what my eyes have just watched—and then re-watched. And I don’t really know if I want to make much sense of it, or if I just want it to remain a blur, a memory that’s only mine.

But here I am, trying to come up with words to adequately describe the greatest Roland Garros final of at least my lifetime.

To me, this match was a movie—with a trailer, and two intervals. And I’ll be talking about it as such during this… whatever.

THE TRAILER:

These were the first six games to me. Almost always, these big matches don’t start off with the highest quality, nerves of the moment typically taking over. but to me, this is the part where I always look out for the tactical adjustments made by both players, as the legs are the freshest, and the mind still remembers what it's supposed to do.

Let the end of the sixth game be the cutoff point of this trailer. At that point, the score was 3-3, but it should have arguably been a lead for the Spaniard. Out of the two players, he was the one who, to me, started off better. He reached break points in each of Sinner’s first three service games, as the Sinner forehand looked shaky. But Carlos only converted one of them...

He would finally convert on his seventh chance, as the constant pressure paid off. By now, one thing was clear.

Alcaraz and his team had made a conscious effort to start the match by targeting the mechanically enhanced Sinner second serve. Why do I say “mechanically enhanced”? Well, because it was once a targetable point of the Italian’s game, one he completely reworked, to the point where it can now be a weapon. But under the pressure of a big final, Carlos took the fight to it. That might have caused him to miss makeable returns with another approach, but it planted a seed of doubt in Jannik’s head.

Carlos deserved the early lead, but quite unsurprisingly, he couldn’t maintain it, as he got broken the very next game. Sinner finally found some rhythm off that forehand and started moving his legs better—hence ending the trailer, and starting the main event.

PART I:

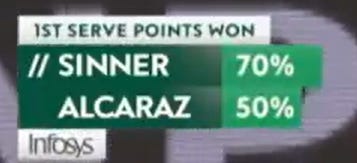

I had talked about in the preview how the serve-return dynamic in this match has been so fascinating because it should favor Sinner, but has historically tipped in the Spaniard’s way in this match-up.

I also did a breakdown of Sinner's new return position, and how I felt that was done keeping in view the above dynamic. It was fair to say that the new strategy worked, as Sinner started to rush Carlos off typical ad kickers that had previously been bankers for Carlos.

The deuce slider was also dealt with better than before, but it's important to note that these adjustments are usually done to neutralize, not to eradicate.

Carlos would eventually drop the first set, and although losing the set was not ideal, it didn’t deter my pre-match prediction. I knew this was basically a four-set match, with Carlos needing to win three before Sinner could get two, mainly due to Carlos's erratic nature and Sinner's incredible base-level play.

Carlos actually had a solid return game to start the second set, and although Sinner did hold serve, it was a sign that Carlos was still there mentally. Until two devastating returns by Sinner in the next game, which opened the door for the Italian, and he capitalized on his first chance, getting the early break lead.

And unlike Carlos, Sinner did consolidate his break, serving a low-percentage but highly effective first serve, as one thing was clear: for the first time since Miami '23, the Italian seemingly had the serve-return advantage.

The set was looking like a regulation 6-4 for Sinner, until he flustered while serving it out. But although that gave Carlos a chance to steal the set, Sinner would ultimately wrap it up in the tiebreak.

The majority of the points were being played at Sinner's pace—baseline, linear exchanges, with very little variety or spin change. This is a pattern that stayed true pretty much the majority of the match, and makes the result even more remarkable to me.

The last act of this part was the opening to the third set, where Sinner played a suffocating game of deep baselining to break Carlos and put one hand on the trophy... little did anyone know.

PART II:

Something shifted. I still can’t quite pinpoint what exactly (the Carlos forehand), but it happened in the very next return game.

Down 0-30, just 18 points from defeat, the Alca-fearhand took charge, producing a couple of clean, thunderous blows to get the break immediately back. Carlos would ride that hot streak, while Sinner, perhaps sensing the finish line too early, made a few uncharacteristic mistakes of his own. Suddenly, Alcaraz reeled off four straight games from the brink of defeat.

The forehand was the hero of that stretch, no question, but don’t overlook the backhand, especially in the game to go up 4-1. Against the best in the world, it more than held its own.

It would be Carlos’s turn to fail while serving it out at 5-3, but he made immediate amends. In the very next game, he unleashed three forehand winners. each a different flavor: a pass, a down-the-line, and a volley. to break Sinner for the third time in the set and bring the match fully back to life.

The fourth set is where this match began knocking on the door of all-time great Slam finals. Sinner found new life, and Carlos did everything he could to hold him off.

Alcaraz couldn’t find a first serve. Down break point in his very first service game of the set, he pulled off what I think is one of the most under-discussed, yet crucial points of the match.

The ball kissed the very back of the baseline. He survived—for now.

From there, Sinner began to coast on his service games, dropping just two points across his first three, compared to Carlos’s seven. That pressure, compounded by Alcaraz’s continued struggle to land a first serve, would prove too much. Serving at 3-3, Carlos was broken to love.

Both in Rome and in the preview to this match, I talked about how Sinner’s running forehand would be a key in this matchup. And in this final, it held up better than I’ve ever seen it against Carlos’s heavy, spin-laced whip on clay. It’s no exaggeration to say: had Sinner won this match, this shot would have been a reason why.

With blood in the water, Sinner produced a run of points that felt pulled straight out of a PlayStation cutscene. He refused to miss, going on a stretch of 11 points won out of 12 played.

And then… came the scorecard seen around the world.

What is a choke?

To fail to perform at a crucial point of a game or contest as a result of nervousness. It’s a term used far too often—often carelessly—overshadowing the greatness happening on the other side of the net, field, or court. It’s a word I don’t particularly like to throw around. After all, everyone is nervous at crucial stages of a big event; not every error under pressure should be labeled a “choke.”

So, did Jannik Sinner choke here? Undoubtedly, yes.

The first match point miss is acceptable to me. Both players were playing slightly passively. Carlos took the initiative, stretched Sinner out wide again to the forehand, and the Italian missed the reply. One down. No choke.

The third match point? You can live with it, too, though we’re testing the edges here. Carlos, on the full stretch and run, hits a forehand that probably kisses the baseline. Sinner was the aggressor in the rally and lost it. That’s sport. Still not a choke.

But I skipped the second one on purpose. That, ladies and gentlemen, was the literal definition of a choke.

Carlos finds some depth but misses his spot on the second serve. It lands squarely in Sinner’s backhand strike zone. And Sinner… just misses the return. Nothing forced, nothing disguised. He had the point and the match in his hands. He failed to perform at the crucial moment because of nerves. He choked.

Carlos followed that reprieve with an ace at deuce, and then a Nadalian forehand down the line at advantage. Just like that, he snatched back all the momentum, all the energy, all the cheers.

At that point, everyone watching knew Carlos was going to throw the kitchen sink into the next return game. And that’s exactly what he did, winning 4 of the next 5 points, breaking Sinner as he tried to serve out the championship, likely still wondering how he wasn’t already giving his winner’s speech.

Ten minutes later, we were heading to a fourth-set tiebreak. To Sinner’s credit, he didn’t collapse; he fought, going up a mini-break and leading 2-0.

But by then, the Carlos train was rolling. The snowball was already barreling down the mountain, and the score hardly mattered anymore.

The next three points? Alcaraz forehand winner. Ace. Another ace.

That was, for all practical purposes, the end of the tiebreak.

And with that, we entered the finale.

THE FINALE:

The doors that were once being knocked on were now slammed open, as the match entered truly all-time great territory. Alcaraz, with all the momentum, much like last year’s semifinal, broke in his first return game, leading in the match for the first time since that early break in the first set. It was a complete takeover by what is, right now, the greatest weapon in the game.

At this stage, to be honest, I thought the match was over. Carlos was peaking. Sinner looked to be struggling both physically and mentally. The match felt done. But Sinner would keep the pressure on Carlos’s serve, which nearly paid off in the fourth game of the set.

The next half-hour of tennis took this match firmly into the Top 10 Slam Matches of the Millennium conversation. It had everything—drama, suspense, shotmaking of the highest order, unbelievable gets and defense, and most importantly: the heart of two champions.

Sinner was up in a return game thanks to a couple of great returns, when Carlos pulled out his most trusted Plan B—the drop shot. Sinner’s legs were tired, and he was likely mentally fried too. Heck, I was just watching the match, and my head couldn’t function properly. The drop shot was perfect, Carlos didn’t even follow it. The ball bounced once, and just as it was about to bounce again, it was greeted by a Head racket in full stretch. The get was jaw-dropping. The redrop was exceptional.

Sinner broke back. Remarkably, this was the fourth time someone had failed to serve out a set in this match. It's quite crazy that no set ended with either player serving it out; two sets ended in breaks, and three went to tiebreaks.

The next game was the perfect precursor to what I truly believe is the greatest single game of tennis played in the 2020s.

Serving at 5-6, Carlos’s legs were completely gone. We were in the sixth hour of the match—no rain delays, no toilet breaks, no MTOs taken by either player. It was just tennis. And only tennis. When Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner gave us this game from the gods.

I could honestly write a complete thread just about that game. But I want to highlight two points in particular—moments where both players went blow-for-blow, like an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object.

And this one topped it…

By the end of the game, which featured 4 winners, 4 induced errors, and just 1 unforced error, both players somehow had their legs under them again, catching a second (or maybe third) wind, as we entered the match tiebreak.

What is a peak?

The point of highest activity, quality, or achievement. You can define it. But how do you quantify it?

I’ve always believed it’s a subjective term dressed in objective clothes. What you value higher in your assessment of performance, I might not. So does that mean there are individualistic peaks?

Tennis, to me, is a game of attacking a fuzzy yellow pressurized sphere within a defined boundary—and then defending it when it comes to your side. That’s the most basic definition I can come up with. And I’ve always said—and believed, deep in my heart—that although it’s close (say 98 to 99), Carlos Alcaraz has a higher peak than Jannik Sinner.

The final set tiebreak told me that, according to my definition of tennis, my eyes were right.

Sinner hit just two unforced errors in that tiebreak. He lost it 2-10.

Could he have played some points better? Sure.

But was there much he could do when Carlos went Oppenheimer mode with the weapon that, to me, defines true talent, shows variety, and—when the going gets tough—ultimately pays the bills? Nope.

The tiebreak was over inside a couple of points. Everyone knew it. Sinner did. Carlos did. The coaching teams did. Agassi did. The commentators did. You and I did.

The final points were just a setup—a pre-ceremony to a coronation.

And how poetic, that in the first Roland Garros ever with Nadal immortalised, his heir apparent hit a down-the-line passing forehand… to commence the celebrations.

NOTES:

Firstly, to start off, what an incredible effort by both players. As someone who got into tennis because of the Big 3, I’m genuinely glad we now have a matchup on tour that rivals that same anticipation and enthusiasm. I firmly believe this would easily rank as a top 5–7 Big 3 match as well, produced by two players I fully expect to end their careers at least in the end stages of the Tier 2 all-time greats. And to get there, they need each other.

There’s a reason why Carlos can go from coasting through long stretches of matches to locking in with laser focus whenever he faces Jannik. And there’s a reason why, even as the current No. 1 player in the world, Sinner isn’t prideful enough to ignore the adjustments required to face Alcaraz. The best rivalries are built on mutual recognition, where every point feels like it will be recorded in the sport’s history books, and this is just that. This rivalry had its magnum opus in New York three years ago. On Sunday, it gave us its Koh-i-Noor.

What adjustments were made?

Sinner had to do two things better than in previous meetings to have a real shot at this title:

Manage the serve-return dynamic more effectively.

Have an above-average day on the run with his forehand.

He did both. And he was one point away from what would have been the greatest victory of his career.

Carlos, meanwhile, needed this Slam more. Sinner already had one this year, and has two more coming up in conditions that suit him better than clay. Alcaraz, on the other hand, was looking to complete something historic—he became just the second player in the Open Era to win four consecutive natural surface Slams.

In the end, after the bottle job, the difference came down to one thing: shotmaking.

Sinner was +19 in the fifth set. Carlos? +23.

I understand that many will say Sinner should have won this final—and in a narrow sense, that’s fair. But this should not be a discouraging loss. Going the distance with your biggest rival, on his preferred conditions, is not a negative result.

There’s been a lot of speculation about how Sinner will respond to this loss. Personally, I don’t see any mental collapse coming. I fully expect him to bounce back in Halle itself next week, and he’ll still be a top 2 favorite heading into Wimbledon.

Will Sinner ever beat Alcaraz?

Absolutely. This will be a competitive rivalry when it’s all said and done. In fact, out of their last five meetings, four have been very close, and all four have gone to the same player. Statistically, that’s unlikely to continue.

Looking Ahead

If you ask me:

Alcaraz needs a Wimbledon title more dearly.

Sinner needs a win over Alcaraz more desperately.

If they meet again in the Wimbledon final—which I think they will—expect more fireworks. Maybe not as high as in Paris, but high enough.

At this point, both players know each other inside out. Tactically, nothing should surprise the other anymore. I’ve written two previews and now a full review of this matchup, and unless one of them adds a completely new dimension to their game, I don’t expect major tactical shifts in the near future.

On Comparisons

I’ve seen some comments saying this rivalry is already better than “Rafole,” or that one of these guys is a better clay courter than... You know who.

On the latter: Don’t even think about it.

On the former: It’s subjective.

Tennis has evolved into a pure power game, which makes matches appear faster. Comparing Sincaraz to Rafole and concluding that one feels more intense or faster is not rocket science.

Rafole had:

Better defense.

More patience.

Less aggression.

Put those three together, and their matches often felt more like chess. Sincaraz, by contrast, is a firefight, and probably more aesthetic to a neutral viewer.

So, who’s the best player in the world?

On hard courts: Jannik Sinner.

On natural surfaces (clay & grass): Carlos Alcaraz.

Sinner’s preferred conditions make up more of the season, and that’s reflected in the rankings. That’s why weeks at No. 1 matter—but they’re not the be-all and end-all stat for me.

And finally, how would I ever know if someone made it here?

If you did, thank you. I try my best to keep biases aside and just talk about how I see this sport.

Ciao! 🎾

Great review, I'm curious about one thing, the best player in the world debate as you said is nuanced because Carlos rules on natural surfaces and Sinner rules on hard courts. How far do you think Carlos is from Sinner in hard courts? After Sinner became world number 1, their grand slam matches on natural surfaces have been very close. Alcaraz has shown to beat him at the US Open and although it was pre Sinner world number, I still think it shows Carlos' level in a hard court fiver setter. I specifically want to see him in an Australian Open final against Sinner because Carlos has been very poor in that tournament and he needs that career grand slam. Carlos always seems to raise his level against Sinner and I trust him to play more consistently against him. So how do you think that would play out and what does Carlos need to improve on to close the gap? Thanks, and keep up the good work.

An amazing review of an epic match. Great work 👏🏽